It’s a question I ask myself almost everyday, and I will try to answer here:

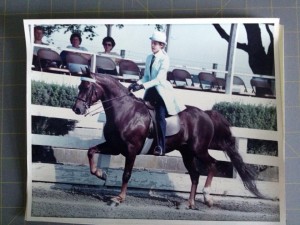

1. Because I’ve been thinking about my childhood a lot these days. I guess it’s inevitable; my daughters are 3-and-a-half and one-and-a-half-years old, and I often find myself comparing their experiences to mine. Horses dominated my childhood. My mother says I rode a horse before I could walk (and also fell off a horse before I could walk). I competed in my first horse show when I was nine-months old. “Competed” might be generous—it was a lead-line class, and my mom tied me to Buddy the Shetland pony’s saddle. After, the judge told her, “People like you make me very nervous.”

Most of my memories from childhood involve horses: sitting in a warm corner of fat J.P.’s stall while he ate his hay; struggling to teach Mercury how to canter, and how to walk; sitting on tall Patrick while he stood on the crossties and my mom cleaned his stall. Sharing a seat with my friend Jess during 4-H club meetings in the cramped, smoke-filled tack room of a local stable. Steering trusty old J.P. along the wooded trails behind my parents’ house. My sixth birthday party (I swear I remember it) when all the kids from my kindergarten class took turns riding Patrick. Listening to my aunt Mary’s wild stories about her years showing Tennessee Walking Horses. The porta-potties near the stables at Quentin Riding Club. The French fries at Quentin Riding Club. That time Mercury stumbled, fell, and

rolled over on me. The way Mercury would scrape my right leg against the fence (any fence—I still have scars). That time Mercury freaked out during a pleasure class at the Mid-Atlantic Morgan Horse Show and I had to dismount and disqualify myself. That time Mercury and I placed third at the Pennsylvania State 4-H Show, but my mom missed it because my Poppy was in the hospital. The softness of Mercury’s nose, the way Mercury listened to me when I talked, talked, talked. The way Mercury was my best friend.

Whether or not my daughters love horses is up to them. If they never hold a pitchfork or a hoofpick, I won’t be upset. As far as I’m concerned, they never need to see the inside of a showring or win a ribbon. But the only childhood I know was a childhood filled with horses. Without horses, it felt like something was missing.

2. Because the horses needed a home. The two eighteen-month-old horses we adopted, a filly and gelding now named Rosie and Ranger, were two of about 50,000 feral horses living in Bureau of Land Management holding facilities. These federally managed horses, known of course as mustangs (from a Spanish word for stray livestock), live on the range in designated “Herd Management Areas” on public lands in ten western states. They may be descendants of Spanish colonial horses, ranch horses, cavalry horses, or work horses—basically, they could be descended from any horse that wandered away, was stolen, or was “set free” from anyone who went west in the last 500 years. These horses share the public lands with wildlife as well as domestic livestock such as cattle and sheep. Ranchers can buy grazing permits to use these lands to fatten their herds. There could be as many as another 50,000 feral horses on these lands, although some dispute that number. Scientists say that the range can support about 26,000 horses; the BLM, charged with managing the horses, tries to reduce their numbers through periodic “gathers,” or round ups. Many of the rounded-up horses are then offered to the public for adoption. The adoption fee is $125.

As you can probably guess, just about everything to do with this is controversial—everything. Even choosing to call the horses “feral” instead of “wild” is controversial. The round-ups, the adoption program, their protected status under federal law, their population numbers, their relationship with cattle and wildlife. I have opinions about some of these controversies, and some I am researching further. I’ve become fascinated. I’ve probably become obsessed. My office walls are covered in whiteboards, which are covered in notes, diagrams, and lists. Yes, I’m writing a book about all this.

3. Because Rosie chose Laurel. The BLM holds periodic wild horse and burro adoption events across the country. Last summer, we attended an adoption event in Lorton, Virginia. Horses and burros were trucked in from points west and unloaded into temporary corrals set up in a pasture. I’d been surprised how quiet the horses were; they calmly grazed and drank, and occasionally came close enough to the fence for people to touch them. The horses and burros were beautiful, of course—duns, roans, bays, paints, greys, sorrels. I walked around all the corrals, taking photographs and enjoying being so close to the animals.

And then something happened. If I hadn’t seen it, I may not have believed it. Laurel walked up to one of the corrals. From across the pen, a young filly (who would become Rosie) saw Laurel and made her way over to the fence. Laurel reached through the fence and touched the horse’s neck; it made me nervous and I almost stopped her, but the filly enjoyed it. So did Laurel. “I think this little mustang loves me. Yes,” she said, petting her neck, “she does love me.” When we returned to the event the next day (after a night of camping at a nearby park), the same thing happened. “There’s my little mustang,” Laurel said, as they both approached the fence. “Hi, little mustang.”

For the next few months Laurel talked about the horse: “What’s my little mustang doing right now? Does my little mustang still need a home? Are the other horses being mean to my little mustang? I love my little mustang so much.”

I probably should have told her that her horse had found a nice home. Instead, I contacted the BLM. Her horse hadn’t been adopted. She’d been sent to a holding facility in Illinois. So, according to the BLM’s adoption specifications, Jesse got to work building a three-sided barn on a nearby farm owned by a friend’s nonprofit organization. We purchased corral panels, gates, hay, buckets. Oh, and a horse trailer. (It’s on our credit card—yikes.) In November Jesse, Laurel, Cora, and I made the 10-hour drive to southern Illinois and brought Laurel’s little mustang home. Because the filly would otherwise have been the only equine on the property, we adopted a second horse, a bay gelding with a delicate, curious face. I chose him because he was the same age as the filly (the BLM will only load horses of similar age and size together), and because he came closer to me than other yearlings at the holding facility. And he had a touch of Mercury about him—up-headed, dark, perhaps a bit high strung.

Since bringing the mustangs home to West Virginia, I’ve been working on gentling them, on getting them to trust me. Rosie is coming along well; she was born in a holding facility to a mare from Salt Wells Creek, Wyoming, who was pregnant when rounded up. I can take her halter on and off, groom her, and pick up her front feet. And sometimes the back feet. We’re working on leading and backing. Ranger, the gelding, is a lot more nervous than Rosie; he spent the first year of his life in the wild with his herd in Fish Creek, Nevada. I still can’t touch him anywhere besides his face, and while we’ve made baby steps towards a partnership, we have a long way to go. But it’s OK. I’m not in a hurry. I’m hoping to build a solid foundation with both horses; that’s my goal for now.

Apologies for the long blog! I will try to write about our progress often. It’s been an adventure. And it’s just the beginning.